![]()

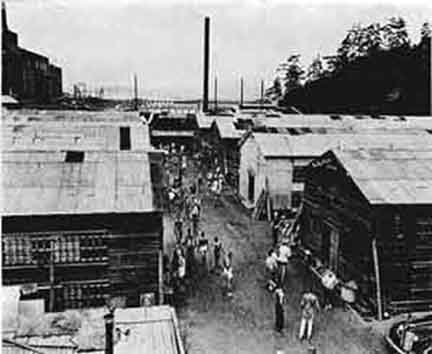

Photo above taken mid September 1945 at time of rescue.

Photo below courtesy of Roger Mansell. The photo was taken by Norm Adamson, a B-29 pilot of the 500th Bomb Group while on a food drop mission. You can see the markings left center. (These photos are of the camp location after it was moved from the White House/Citadel location in March of 1943.) The camp consists of the long buildings to the right of the power plant with the smokestacks.

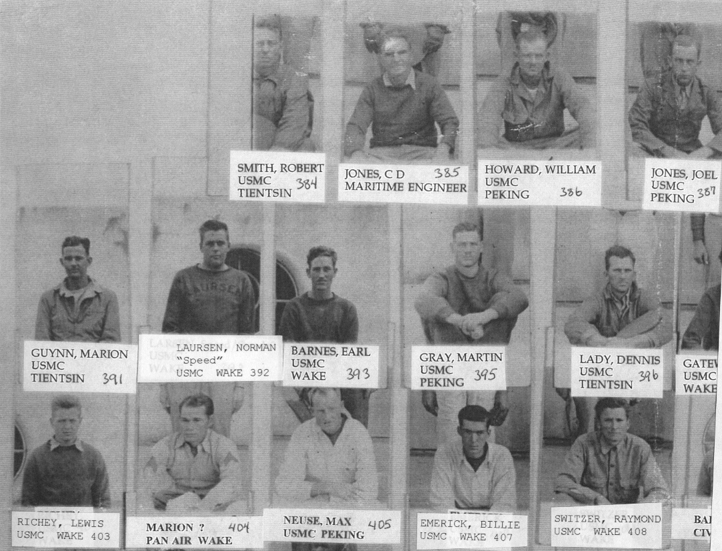

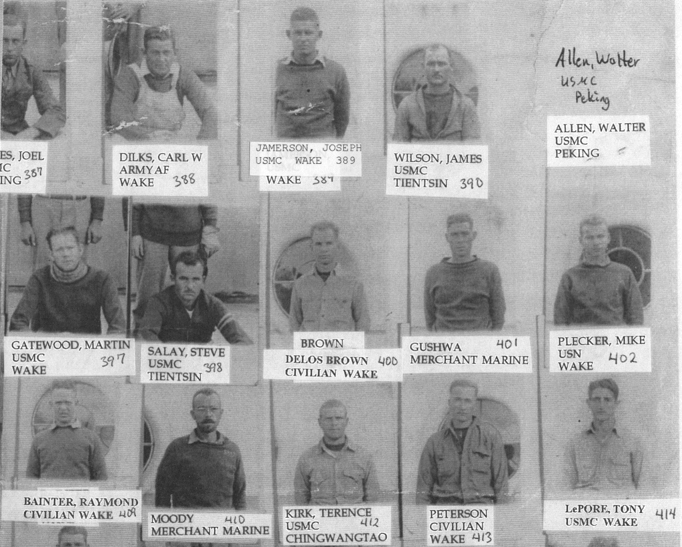

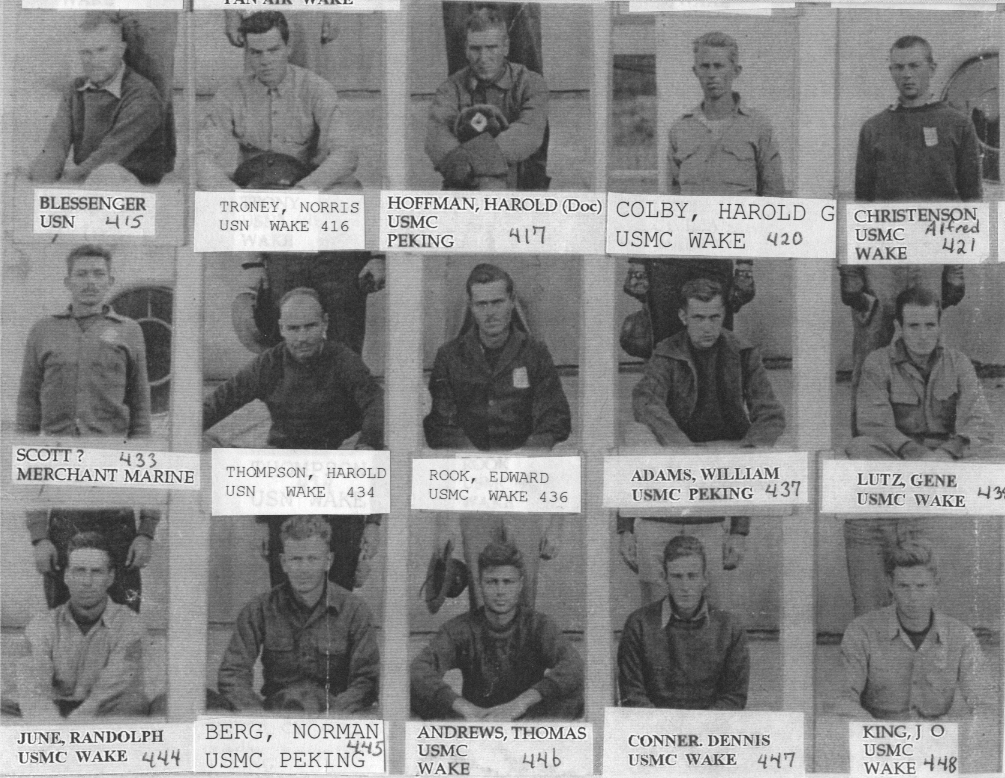

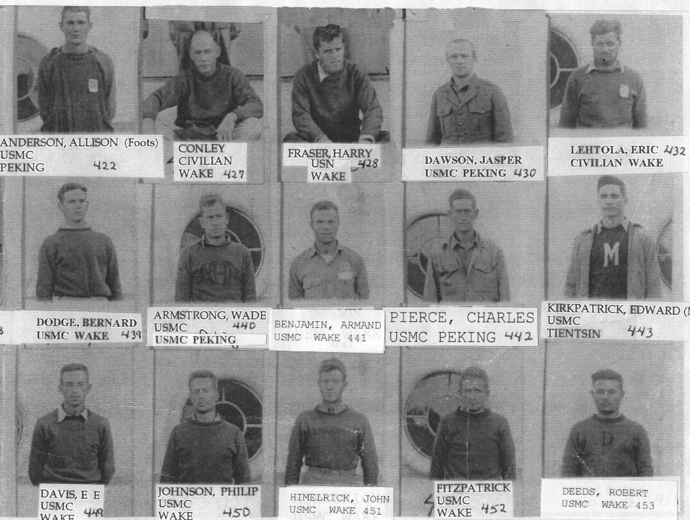

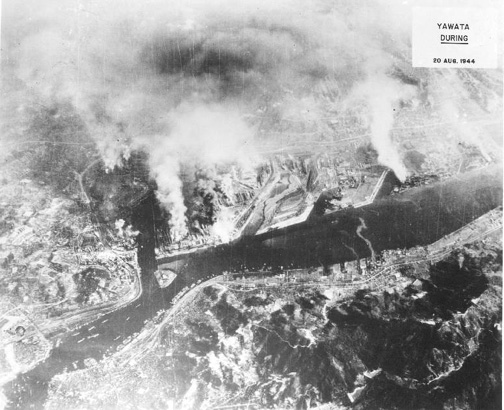

This camp was designated as Camp 3-B Yahata Seitetsu in September of 1942. Yahata, sometimes spelled Yawata, was the city, Seitetsu refers to iron works as Yahata was part of a huge industrial complex sometimes called the "Pittsburgh of Japan". This area was later the target for the first B-29 raid on Japan. Yawata is at the northernmost tip of Kyushu, just across the narrow strait from the port city of Shimoneski on the island of Honshu. On 23 September 1942 the camp was established at Yahata as the Yahata Provisional POW Camp and occupied by American civilian POWs sent in September from Woosung, China. On 5 November 1942 another group of POWs, most of them military, arrived from the POW camp at Woosung, China. The building which housed the POWs was called the White House by some of them, perhaps the Citadel by others. This group from Woosung included at least 25 North China Marines and 25 Wake Island Marines. Six civilians, also captured on Wake, 4 Navy, 3 Merchant Marine, 1 Army Air Force, and 1 Pan Air employee were also part of the group from Woosung. There were about 70 POWs in this group. The earlier group sent from Woosung in September 1942 apparently consisted of about 70 civilian POWs from Wake. They probably helped set up the camp to ready it for the larger groups of POWs to follow. Included in the November 42 group of POWs from Woosung was Navy Chief Barney D. Prine, who had enlisted in the Navy in 1907. Three other former first class petty officers included "Heiny" who owned a restaurant in Shanghai and Tony (Daniel?)Colilla, originally from Brooklyn. These men were from the gunboat Wake. (Dennis Connor oral history-U of Missouri at Columbia) On 1 January 1943 the camp was renamed Fukuoka POW Camp. On 1 March 1943 it was renamed Fukuoka 3-B. On 15 December 1943 the camp was moved to Kokura. On 13 September 1945 the camp was closed. (The dates of 15 and 17 September are also used by various sources.) All the "guests" checked out that day and went home. North China Marines Marion Guynn and Terence Kirk and Wake Marine Dennis Connor (with Wake Marines Armand Benjamin and Gene Lutz) had already left the camp and reached US forces. They left separately and in each case with other POWs, but they cannot remember who was with them.

The book "First Into Nagasaki" by George Weller (published 2006) has war correspondent George Weller encountering North China Marine Walter Allen after Allen had left Fukuoka 3-B accompanied by Albert Johnson of Geneva, Ohio, Hershel Langston of Van Buren, Kansas and Morris Kellog of Mule Shoe, Texas. These three are listed by Weller as being crew from the oil tanker Connecticut. The official list from Fukuoka 3-B has them being crew from the SS Stanvack.

Weller also tells of meeting Edward Matthews (from the destroyer Pope) of Everett , Washington, Charles Collings of Northeast, Maryland, Miles Mahnke of Plano, Illinois, Albert Rupp of Philadelphia and William Cunningham from the Bronx (both crew on the sub USS Grenadier), Vetalis Anderson of Denver, William Blucher of Albuquerque, and PhM Stanley Shipp of Hay Springs, Nebraska. All had left Fukuoka 3-B before US forces arrived. In some camps men who left early were threatened with a court martial. All of these names are not on the official list. There are some missing names from those lists, in some cases because the men had left the camps long before US forces arrived and the official lists were compiled. Sometimes the POWs left their camp and were at another camp when US forces arrived to evacuate them. Their names then appear on the roster for that second camp, not the one they were actually held at.

William Adams, Walter Allen, Allison Anderson, Wade Armstrong, Norman Berg,

Jasper Dawson, Henry Elvestad, Chandler Fouche, Martin Gray, Marion Guynn,

Harold Hoffman, William Howard, Joel Jones, William Killebrew, Terence Kirk,

Edward Kirkpatrick, Dennis Lady, George Lindsey, Max Nuese, Charles Pierce,

Steve Salay, Alvin Sawyer, Marino Simo, Robert Smith, James Wilson

Civilians Delos Brown, Raymond Bainter, Robert or Roland Peterson, ?Conley (Harold Connally, William Connolly ??), Eric Lehtola,C.D. Jones-Maritime Engineer, Carl W. Dilks-Army Air Force(captured on Wake), Frank Gushwa-Merchant Marine, ?Marion-Pan Air, Barnard Moody-Merchant Marine, Robert(?) Scott-Merchant Marine

The above names may or may not be complete for North China Marines at Fukuoka 3-B. Wade Armstrong was sure no other North China Marines came to the camp after the original group arrived about 5 November of 1942. Dennis Connor said the same. Wes Injerd has published on his site (see Links) the rosters of all Kyushu camps. No other North China Marine is on any of those rosters. In fact, some of those names known to have been at Fukuoka 3-B are not on those lists. This leads me to believe the above list is close to completely accurate. Just who was in the original group sent from Woosung in November of 1942 is slightly unclear. The pictures, camp roster, and list of deaths gives us the names listed above. Sgt William Killibrew died 10 Feb 44, cause of death listed as acute pneumonia. This is discussed in Kirk's book The Secret Camera. Max Neuse died on 13 Dec 44, cause of death listed as beri-beri and croup pneumonia. This is mentioned in Kirk's book and in the trial record of the camp commander. This record refers to brutalities by civilian employees and guards at the Yawata Steel Mills. On 5 November 1944 there was "alleged" mistreatment which contributed to the death of Max Neuse by beating with heavy tongs. The commander was found not guilty of this charge. A sworn affidavit by North China Marine Alvin Sawyer concerning this beating can be read on the Escapes and Deaths page.

Corporal Harold A. Hoffman discussed Fukuoka in an interview with his church school in Feb 1946:

"the doctor (Japanese) in the medical department felt you for fever with gloves on - when he thought you were faking sick you would get slugged in the jaw. When you were really sick your rations were cut and the guards would say "tomorrow, maybe next day, you die". Barracks full of bed bugs and fleas. We learned one can live on less food than you can probably imagine. A person can stand more than we ever think. We had no heat in our barracks. We warmed up by rubbing ourselves with towels.

If shoes were not lined up straight the worst beatings would follow. When the POWs broke into a building to get at Red Cross food and supplies the Japanese used water torture on some (tied on a ladder with your head down and water poured down your nose) and others were thrown in a water tank (in the winter). We learned a man can take an awful beating. We were told we would work for the Japanese for the rest of our lives and after the war we would help them teach the barbarians in the US how to live. Received my first letter in June 1944. It had been written in June 1942. Received five or six letters during the whole time as a prisoner.

When B-29s dropped food at the end we ate heartily. In a week people looked altogether different."

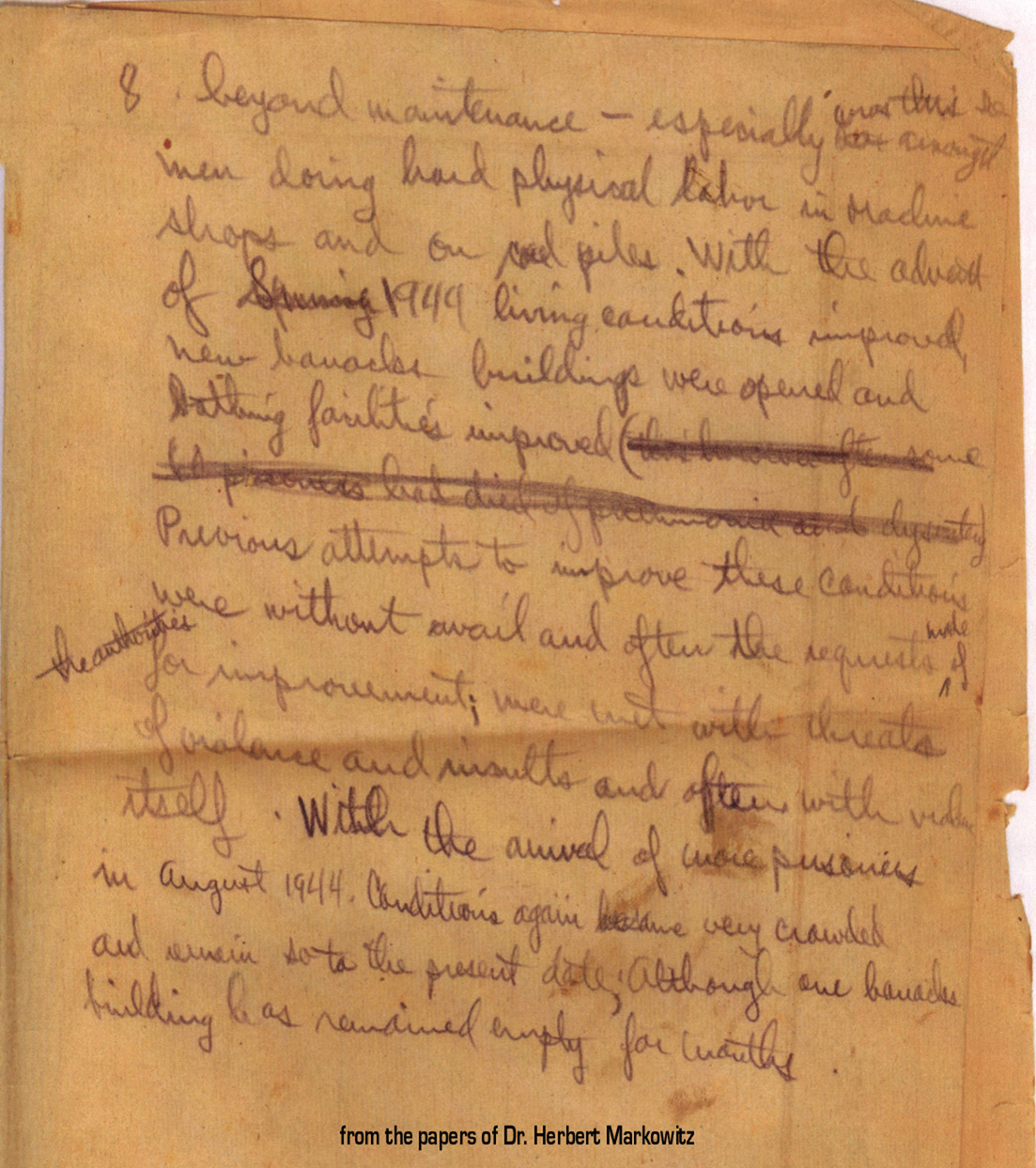

Below is a page from a log kept by Navy Dr Herbert Markowitz (captured on Guam). It appears through the courtesy of Mrs. Herbert Markowitz and the efforts of North China Marine Marion Guynn and Abe Shragge from the Univ of San Diego.

Herbert Markowitz

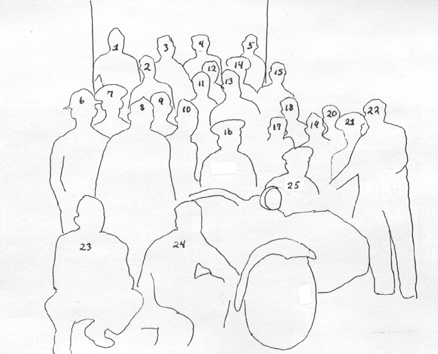

1. Harold "Doc" Hoffman 2. Marino Simo 3. William Adams 4. Allison "Foots" Anderson 5. James King 6. unk 7. Charles Pierce 8. James Fitzpatrick 9. E E Davis 10. unk 11. unk 12. Thomas Andrews 13. Lewis Richey 14. Edward "Moose" Kirkpatrick 15. Joel Jones 16. Norman "Speed" Laursen 17. Tony LePore 18. Edward Rook 19. Robert "Rocky" Deeds 20. Del Brown 21. James "Duckbutt" Wilson 22. William Howard 23. Alvin Sawyer 24. Henry Elvestad 25. Navy Dr. Herbert A.Markowitz (captured on Guam)

It appears one of the unknowns is PFC Philip W Johnson but I do not know which one.

Norris Troney Diary from Fukuoka 3-B

An excellent series of photos of the camp and POWs taken in the middle of Sep 1945 just before the camp was finally closed. Do not miss these photos.

Steve Salay affidavit submitted for trial of camp commander.

_____________________________________________________________

The link to the following is no longer working so I copied the text below the next photo.

www.wwiihistoryclass.com/education/transcripts/Kramp_C_005.pdf

Transcript of an interview with an Army POW, Carl Kramp, captured in the Philippines and sent to Fukuoka 3-B. Probably the best description of life in Fukuoka 3-B. The camp is referred to as Uwada. This is a misinterpretation of Yawata. Details such as the Navy doctor, English and Dutch prisoners, amputation caused by US bombing at the end, and transfer from Nagasaki on an English aircraft carrier all identify this as Fukuoka 3-B.

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

1

Question: Just so I have it on tape, the first thing I want to do is just to get your first and

last name so I have proper spelling of that.

Answer: Hm-hmm.

Question: So if you'll go ahead and give me first and last name and the spelling.

Answer: Carl, C-A-R-L, middle initial M, last name is Kramp, K-R-A-M-P.

Question: And you served in which branch?

Answer: Army, US Army.

Question: US Army.

Answer: Hm-hmm.

Question: So when did you -- did you enlist, drafted, how did --

Answer: I was enlisted in National Guard, May 11th of 1940. I went into the National

Guard. And then in September, it was, why we was changed to -- we was the 34th Division,

34th Tank Company, 34th Division in 1940. And in 1941 -- '40, why, they changed it, in

September they changed it to Company A of the 194th Tank Battalion. And that took in a

battalion, a company out of St. Joseph, Missouri and a company in Salinas, California

Answer: And then in February 10th, we were inducted in the federal service and sent to

Fort Lewis, and we trained at Fort Lewis. And in September of '41 we was sent to the

Philippine Islands. Company B was sent to Alaska, so they split us up. And from there, why it

was rough. (laughs)

Question: Now you were just a kid at this time -- how old were you?

Answer: I was 20.

Question: Twenty. So that's pretty much just a kid.

Answer: I had my 21st birthday out in the middle of the Pacific. (laughs)

Question: Heck of a birthday party they threw for you -- one that went on for awhile.

Answer: It went on for awhile, yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: So when did you first see active duty? I mean when did you first see

battlefront?

Answer: On December the 26th of '41. We was on the -- moved in the front lines on the

25th of December. And then the 26th, why the Japanese attacked and they surrounded us

and we had to go through them to get out. And I was lost. I was missing in action, because I

was supposed to follow the tank ahead of me, but I got hit with a shell, hit right in front of me

and I looked through a little peep slot about that wide -- (gesturing) -- about that long and

about that wide. And explosion inside and out, 'cause we got hit on the back, too, at the same

time, a box of ammunition blew up. Why, it blinded me and I couldn't see where the other

tank had went. So when the other tank, I couldn't see it anymore, I took the first road that I

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

2

could see out of there. I figured that would be best thing to do (laughs) and we got back all

right.

Question: So it might have been an advantage that you couldn't see --

Answer: We did, because the rest of the tanks were all lost because the Filipinos blew

their bridges and we had no engineers. And so they couldn't get the tanks across and they

had to blow up all the tanks. And they lost our whole battalion lost their tanks there. So.

Question: What's -- I mean, you were pretty young, and I hear a lot of the vets say we

were too young and too stupid to know any different. We were just doing our job. But do you

remember, were you afraid? Did you have any real concept of what you were in?

Answer: Not really. Not at first. Not until the first fellow was killed. Then we realized

that they were shooting at us and somebody was going to get killed. When the first guy got

killed I -- then we realized that something -- it wasn't any fun anymore. Because we was

walking around with no steel helmets on or anything. And the mortars were flying over ahead

of us and machine gun bullets were going over the top of us, and one thing and another and

didn't even bother us until the first guy was killed. Then we realized what was going on. Then

we woke up to the fact that they wanted -- they were trying to kill us. Cause otherwise, why,

like firecrackers (laughs).

Question: Kind of fun until you realize what --

Answer: Yeah.

Question: So did you then just live in constant fear forever, or was it fear and then you

could push that aside --

Answer: No, you don't fear nothing. I mean, you're not afraid. We, well, I played

pinochle on Bataan and the shells were going over the top of us, we'd listen, say, well, that's

not going to come anywhere near us, and we'd listen to another one come over, well, that's

going someplace else. You could tell where they were going to go, you could hear them, and

so it didn't -- didn't bother us any. But, 'cause then, I don't know what it is about it, but a

person gets used to it. And the fear is practically gone. But, so, I don't know, I can't explain it

any other way.

Question: Is it probably because in your mind it wasn't going to happen to you?

Answer: I guess that was it.

Question: What about when you look back on it. Do you have -- in retrospect, do you

have a fear of thinking --

Answer: Well, I do, yes, you do. Now, I have -- I do this darn near every night. You

always think back, what's -- what happened to you. And I hate it. I hate to do it, but my

brain runs back to it. Why, I don't know. And I'd like to be able to forget it (laughs) but it

just doesn't seem to do it.

Question: Now you were captured.

Answer: Yes, hm-hmm.

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

3

Question: How did that happen?

Answer: I was in the hospital. I wasn't wounded but I had boils. So I was in the hospital

and the Japanese left us in the hospital and then they set the big guns around the hospital and

used it for -- So Corrigedor couldn't fire back. We were hostages, you might say. So

Corregidor couldn't shoot back at us.

Question: So human shield.

Answer: We was a human shield, yes, hm-hmm.

Question: And did they remove you from the hospital eventually and --

Answer: After Corregidor surrendered, they did, yes. They took us to Manila

Answer: We were prisoners in Manila

Answer: To prison in Manila

Answer: And then from there we went to Cabanatuan, the main camp. And then we

stayed there until we went to Japan.

Question: Now at that point did fear start to settle in?

Answer: No. You get used to it. You don't know whether you're.. you're going to look at

the next -- guy laying down next to you is going to be dead or not. So you don't -- it don't

bother you. You get to where you don't mind -- it don't bother you. Cause you didn't know

what was happening, one minute to the next.

Question: Now what was your -- what was your treatment like, because, now, the

Japanese didn't recognize the Geneva Convention?

Answer: No, they didn't. They treated us just about the same way they treated their

soldiers. Rough. That was rough. We were treated like that. Cause they didn't make

anything easier for us than they would their own soldiers, you might say, and they treated

them terrible. But at least they got food and we didn't. That was the main thing. We didn't -

- we just got just enough to get by on and that was it. And that wasn't enough to even get by

on, you might say -- just enough to sustain the life in you for awhile cause you get so weak

you slept most of the time. But the worst, worst part was on the Hell Ships. You went on

those, why you remember probably seeing pictures of the old slave ships coming across. Well,

we were now in the same position as that, but we weren't chained, you might say. We had a

spot and that was it. And it was messy down in there because they wouldn't let you out to the

deck to go the bathroom or anything like that. They just put down buckets. Of course

everybody was sick from dysentery, one thing or another and people got crapped on every

night. Was laying down in different -- where they were -- some of them had been walked

across, you know, so people couldn't make it to the buckets they had down in there, why, they

-- guy got messed up. And they put down the rice in a bucket and then they'd take the

bucket out and put it full of water and then you drank sour water all the time. Cause -- and

that's what made you sick. And I remember coming out, getting off the ship at Mogi, Japan,

and -- and we walked down the street and the people on the street was gagging from the

smell of us. Cause it was -- and we couldn't smell it but they could. (laughs)

Question: So that was transporting you from where they captured you to --

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

4

Answer: To Japan. From the Philippines to Japan.

Question: Yeah.

Answer: Hm-hmm.

Question: So now what is your -- how do you survive that? What's going on. Do you take

your mind to other places or do you just focus on minute to minute?

Answer: Just minute to minute I'd say, yeah, hm-hmm. Yeah. You knew that anything

could happen to you at any time but you weren't afraid of it. You got where it was -- you'd

been that way for so long that you just didn't care anymore. You didn't care if you lived or

died. And that was probably the best thing that could happen to a person to get into a

position like that.

Question: What -- now, when the put you in the camp, did they make you work or did

they --

Answer: Oh, yeah, we worked about 14 hours a day, six days a week. They let us have

Sunday off, that was main thing, one thing, but most of the time we worked. We worked hard

too, and it was hard work.

Question: What did they have you do?

Answer: Well, I was working in Uwada Steel Factory in Japan. First we got there, why

they had us shoveling slag out of where they pour the steel from. And that stuff there is

about 200 degrees. Well, they'd let it get down to about 150 degrees and then they'd put us

in there to try to shovel that stuff out with scoop shovels. And in a minute, one minute, you

know, you have to put water on it to cool it down but you worked in steam, you were just

sopping wet all the time. And even in the wintertime, why you come out of there, you're just

sopping wet, you didn't -- you didn't have no coats or anything like, you know, that to put on,

so you just -- freezing all the time. Yeah.

Question: You lived in barracks or what did they --

Answer: Yeah, we lived in barracks, yeah, hm-hmm, slept on a grass mat. The blankets

-- well, I can describe our blankets -- you might as well put a sheet of plywood over the top of

you. They were made out of coconut, and you could roll them up and stand them in the

corner. (laughs) There was no warmth in them.

Question: Did you -- within your group within the barracks, did you form associations with

other POW's or stay to yourself or -- how --

Answer: No, you didn't -- you tried to stay -- I would say, I'll put it from my point of

view. I had friends over there, but we didn't visit because when you got a chance to rest, you

rested. You didn't make no associations or anything like that. Some -- when you got a day

off, you slept most of the day to get your strength back, because that's all you could do. You

didn't have much to eat. They give us rice and barley, mostly, barley and millet, they fed us

toward the last, and if you -- the Japanese would get the bottom of the carrots and we'd get

the tops. So there wasn't much to that. They'd send you over fish soup sometime, but I think

the fish just swam through it. (laughs)

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

5

Question: Not a lot of meat.

Answer: Not a lot of meat, no. (laughs)

Question: If you lost your strength and weren't strong enough to work, I know the

atrocities in some of the German camps, how did they deal with that, or did you even see any

of that?

Answer: You went to work whether you were sick or not. If you're too sick to get out of

bed, they let you stay in, but if you were just mildly sick, you went to work. They didn't have

no -- they just kept you going all the time.

Question: Did you have any association with the guards? I mean, were there different

guards who were nice, and different guards that were mean, or --

Answer: Some of them, some of them -- most of them were mean. But one -- we had

one guy, we called him Shorty. He didn't like the war and he didn't like anything about it. He

let us know that he didn't like the war. He'd say, "I like the United States; I don't like the

war." And he'd take and hide us, sometimes, when -- from the Japanese soldiers and put one

of us out in the guard duty, you know, to watch and see if any soldiers came. If any soldiers

came, we supposed to run back and wake him up so we could get back and show that we were

working. (laughs) He was -- he was -- he was a nice guy, I'd say that much for him. He

didn't like the war and he let us know that, too, right off the bat. If they'd caught him, why

they'd killed him.

Question: So there was this definite human relationship with some of the guards where

you saw that you were brother to brother, I mean --

Answer: Well, you might say that with that fellow, but that was the only one that I knew

of. Most of them were mean to you. They had a little upper hand over an American and they

took it.

Question: Was it -- do you think -- was it a hate for Americans, or was it just they were

given power and they just were corrupted with --

Answer: They were corrupted with power, yeah. That was with the (inaudible) And we,

had -- they were small people and they lorded it over the bigger ones. That was about it.

Question: And I assume they were probably roughly the same age as you were.

Answer: Yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: And they -- they were shoved into this job and --

Answer: Well, these -- the guards were older people. They had been in the Army at one

time or another and had been discharged for some reason or other and that's where they

came from. But, whether they'd been wounded or what, I don't know, but they -- they were

ex-soldiers, and they were the ones that were mean.

Question: Did you ever -- Lauren was talking about this yesterday. He said that it was

real hard to get the upper hand or play a little trick on them once in awhile, but every so often

you found some way to - to goad the guard a little bit. Did you run into any of that or were

you too busy surviving?

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

6

Answer: Too busy surviving, yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: They talked about their schedule. You had to get up because you had to be

counted. Mid-day you had to be counted, and in the afternoon you had to be counted, and so

there was this very regimented. But they didn't work in Germany.

Answer: Well, we worked. We were counted in the morning and counted in the evening

again, but that was it. They didn't count us at noon 'cause we was out working. And we was

slave laborers -- we were slaves, actually. So they didn't bother with us at noon.

Question: How long were you in the camp? I mean, how long were you captured -- I

mean, how long were you a POW?

Answer: About 3-1/2 years.

Question: Wow.

Answer: Hm-hmm.

Question: So in that time you had no contact with any family --

Answer: (shakes head no) I got one package -- one from home and one package, one

letter, from one of my uncles, but I never heard -- the rest of the time we never got

anything. We sent out a card, probably every six months, I think it was, and we were told

what to put on it. We were supposed to be in good health and everything, you know. And --

or they wouldn't send it if you put anything else on it. They had the lockout and we could only

check this or check that, no writing or anything. You just -- just the name of the people it was

supposed to go to.

Question: So you put your name, who it was going to, and then you checked, I'm in good

health, having fun in Japan.

Answer: Yeah, having fun. Yeah, yeah.

Question: Do you know if any of those got to your family or anything like that?

Answer: Some did but not all of them. Hm-hmm.

Question: And then return, nothing, basically got returned.

Answer: No, nothing got returned.

Question: So what was the hardest part for you of being a prisoner?

Answer: Well, the sickness. The sickness, at first. And lost so many of them at first, you

know, I mean, 200 of them a day was dying. (inaudible) and the sickness I had, diphtheria,

yellow jaundice and dengue fever all at the same time. And doctor come -- I remember the

doctor's name, Dr. Schultz, he says, "You're a lucky kid." I says "Why, why am I lucky? I

says, I know what I got." Well, he says, "This is the last shot of diphtheria serum I got". And

he gave it to me and the rest of them came in that day died.

Question: Wow. And that was while you were in the camp?

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

7

Answer: Yes, hm-hmm. That was in the Philippines.

Question: In the Philippines. Okay.

Question: Were you aware of -- of dates? I mean in the fact of -- was it just another day,

another day, or were you aware when, like a holiday, Thanksgiving, Christmas, things that, to

me --

Answer: Yeah, we kept track of that. I don't remember how we did that but we kept

track of it anyway and so we knew when it was Christmas and holidays and things like that.

Question: Did you acknowledge that or did you try to shut that off to survive?

Answer: No, I don't remember any more just what we did about that. We never -- we

had to work on those days, nothing -- it was just -- our holidays and not theirs so we had to

work on those days. But we try to remember them. One thing and another. Sit down and

talk about what you like to eat. (laughs)

Question: You know, that's interesting, because that's what Lauren said got them through

-- food.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: They talked a lot about food.

Answer: Talked about food. Yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: Buttered pancakes with syrup was his --

Answer: Hm-hmm, yeah.

Question: And he says to today -- his wife says to today, he is never going to go hungry.

That was the hardest thing --

Answer: Yeah, that was me, too. I'm not going to go hungry. People don't know what

hunger is. They know hunger -- hungry, but they don't know what hunger is. Hunger is when

you got hungry all the time, and I don't know -- people talk about hungry people in this

country. Well, they're not really hungry. They're -- they're getting something. But hunger is

on the high list -- when you're hungry, you hunger for something.

Question: It sounds like not only were you hungry but you were dealing with this constant

sickness.

Answer: Constant sickness, yeah.

Question: So no, food, no --

Answer: Yeah.

Question: Now, did you -- when you came out, were you pretty skin and bones?

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

8

Answer: No, we weren't, because we was in there a whole month before the Americans

came to get us in Japan there and they dropped food to us, and we were eating day and night

(laughs). We put it on -- weight on pretty fast.

Question: Did you get sick from getting all this food all of a sudden? Was that hard?

Answer: No, we didn't. It was nice to get something to eat, anyway. Had plenty to eat.

Question: What other POW's that were with you -- Germans, English, British, I mean who

--

Answer: There was English, and East Indians, and I think there were some Dutch, too, I

don't know, Dutch, East India, and on like that. But it was mostly Americans. But there was

some English.

Question: Do you keep in touch with any of them?

Answer: No.

Question: No --

Answer: I don't remember their names, even. Just the guys in my company. I keep in

touch with some of those but there's only about eight of us left now so I don't know, some of

them are sick, pretty bad off and one thing or another, but -- I don't keep in touch -- I don't

remember the guy -- we had to double up and sleep together to stay warm, and I don't even

remember the guy's name that I slept with, cause we didn't -- just somebody to keep warm

with, try to keep warm with.

Question: Do you remember how you found out the war was over?

Answer: Well, we was out -- we was out working, and they sent us all back and we heard

all the people standing around their radios listening to the Emperor and we didn't -- we knew

there was something going on but we didn't know what it was. So, I'm glad the war ended

then because we found out later on, oh, about ten years ago now it was, that the Japanese

had orders to shoot us all -- shoot all prisoners of war the first week of September, 1945. So

we were glad the war ended on the 14th of August. (laughs)

Question: Wow. Boy, that's -- that had to be kind of bone chilling.

Answer: Well, we didn't know it until about ten years ago, so it didn't bother us. We

probably found out about it, why, it had been a little different if we had been over there.

Question: Did -- so when the war ended, what happened in the camp? How did you get

out? What -- did you wake up one morning and everything was different or --

Answer: Well the Japanese soldiers left. We didn't have no guards. And so we just went

into their place, and like the medicines and stuff, why the Navy doctor, the day they dropped

the A-bomb on Nagasaki, that was supposed to have been dropped on the Uwada Steel

Factory. And that was the first objective. But they brought it over and it was raining, so they

took it down to Nagasaki and dropped it. But they bombed us out with incendiary bombs. We

were out in the factor working. And this Navy -- one guy had his shoulder, his arm practically

blown off, so the Navy doctor had to take it off with a hack saw and a butcher knife and no

anesthetic. And after the Japanese surrendered they had all kinds of medicines in there and

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

9

anesthetics and one thing and another in their supplies that he didn't even know they had, but

they wouldn't give him anything.

Question: So you were working in the fields for the steel factory and the US came in and

bombed it with incendiary bombs --

Answer: Hm-hmm. Yeah. They hit the -- I was working in the coal field at that time, and

the steel factory I was in before had been bombed out. So they brought me on some of the

coal. Well, they caught the whole coal field afire that day. But we didn't pay any attention to

it. We -- we were sleeping in the little tin shack and trying to -- shrapnel started coming

through the shack and we just put our scoop shovels over our head and went back to sleep

(laughs) You got where you didn't care anymore.

Question: I assume, I mean your mind had to be, if I sit here or if I run or if I crawl, it's all

the same.

Answer: Don't run. Nothing -- you're liable to get hit. Stay down on the ground. Yeah,

hm-hmm.

Question: So once the bomb was dropped, did you get the news of that?

Answer: No, we didn't know what was going on. We knew something had happened but

we didn't know what.

Question: And then did you get up one morning then and the guards had all just --

Answer: Yeah, they'd all left, hm-hmm, yeah.

Question: I heard one gentleman I talked to was saying that the guards left because they

knew that, with the war being over, if they were still around, some retribution --

Answer: Yeah, probably that was true, hm-hmm.

Question: So then you had to -- the war is over, you got some news that the war is over,

or just all of a sudden they started dropping food to you?

Answer: No, we knew the war -- when they left the camp we knew something had

happened. We figured the war was over when they left like that. But otherwise we didn't

know much. They dropped food to us and that was some -- they did send a representative --

I think it was the Navy came in and told us that we had to stay there 'till we were repatriated,

I think it was. And then they started dropping food over us. There was no sign on our

buildings for POW, so they had to put signs on the building, POW's, so they could know where

we were so they could drop food to us.

Question: So like on the roof you put --

Answer: POW, yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: So do you remember the food -- what it was that you --

Answer: Oh, every kind, yeah. I can't remember. It was all canned stuff. There was a

lot of bacon -- I think there was a lot of bacon -- we sure had bacon for quite awhile (laughs).

Carl Kramp

Tape 1 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

10

Question: You didn't care what it was.

Answer: No.

Question: Just that it was food and it was good.

Question: So then after the war ended, it was, again historically a lot of our view is the

war is over and there's these big ticker tape parades and all that. Well, yes, in New York, but

here you are in Japan, war is over and now are you wondering, how do we get home, or --

Answer: Well, we knew they'd come and get us, we hoped anyway. (laughs) We hoped

they'd come and get us and they did, finally. But it was the 16th of September before they

come and took us out.

Question: And how long did it take you to get back stateside?

Answer: Oh, I was back stateside the end of October.

Question: So it was still quite a while.

Answer: Still quite awhile, yes. Went to the Philippines, first and then to -- we went --

went to Nagasaki from there on the train and then we went to Okinawa in an aircraft carrier,

British aircraft carrier, and we was hoping they'd -- heard about Bully Beef -- hoped they'd

give us Bully Beef, and they gave us rice. (laughs)

Question: Just what you wanted.

Answer: Just what we wanted.

Question: I have to switch tapes here.

Tape 2 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

1

Question: For younger generations to really understand a combination of things, of both

sides of war. I mean, there's the atrocities, but there's also things that -- that happened that

we just conceived the war as being really scared and all that. And here you're faced with a

life-threatening situation but yet you found some way to survive.

Answer: Yeah.

Question: You found a strength in it and you know, if I were to write a story I'd say the

bombs dropped and they ran, hiding and scared. Well, now you describe it to me -- the

bombs were dropping and you, you're know, trying to get another couple winks of sleep.

Answer: Yeah, yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: So there's that aspect of war that gets -- gets lost also. One question that I've

always wondered is, for a couple of reasons, is -- once the war -- well, first of all, when you

went over, ok, I'll back up before you became a POW, and you were fighting. Who or what

were you fighting? I mean, in your mind, what -- were you just protecting yourself or --

Answer: No, we were fighting the Japanese. Yeah, hm-hmm. We couldn't -- our tanks -

- our small tanks, light tanks, we couldn't use them as a tanks should be used because there

was just no way through the jungle and one thing and another. For those type of tanks. And

so we discovered that -- as the line folded, as the line kept coming back into Bataan, the line

folded, we would hold the Japanese back until the line would re-establish in another are

Answer: Then we'd retreat. But we were always the last ones out. We stayed. We was

the last ones back. So that's what they used our tanks for -- just to hold the Japanese back,

and it caught up to us a couple of times and we had to fight them but --

Question: What was their technology like compared to our technology?

Answer: Well, I'd say that their tanks were about the same as ours at that time, hmhmm,

yeah.

Question: So you were evenly matched. A It was evenly matched, but -- I never even

seen a Japanese tank.

Question: Oh, really.

Answer: No, I never seen -- because we -- we didn't -- wasn't no tank battles that I can

remember.

Question: Were you close enough that you actually saw soldiers -- Japanese soldiers or

were you kind of separated with your tank.

Answer: I never seen any, no.

Question: So that aspect of the war --

Answer: -- didn't come in this, no.

Question: So when you left -- after you got done with the war, did you leave with an

animosity towards a country or towards a person or what were your feelings in that way --

Carl Kramp

Tape 2 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

2

Answer: Animosity towards the country and I still have it. Cause they treated us bad,

you know. They could have treated us different. But -- like they did the prisoners in the

United States. They were treated decent. Why couldn't they have done that to us. But of

course they didn't have the Geneva Convention, they never signed that, so they didn't have

to. But they -- well, tell you the truth, how they treated their own soldiers. I seen them out

there one day, he was -- this Japanese Master Sergeant was having a walk with this one little

guy. He couldn't stay in step. And this Master Sergeant, hollered at him and hollered and

hollered at him. Finally the Master Sergeant just got mad, he went over there and lopped his

-- and took his sword out and chopped his head off. The next day they had a big funeral for

him. And that's the way they treated their soldiers, you know. When the ships -- they treated

their soldiers down in those holds just like we were. Of course they probably could get out on

deck and one thing and another, but the main thing -- but we couldn't.

Question: That's interesting that they -- that it was a mutual disrespect, I guess, or --

mind set or something.

Answer: Yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: What did you think then when -- cause I remember when it used to be "Made in

Japan" was like terrible stuff, where nowadays --

Answer: Yeah. I don't buy anything that's made in Japan if I can help it. Not nothing if I

can help it, why I won't buy it. Sometimes I can't help it, you need something, you have to

have it, "Made in Japan". But I don't want to buy anything -- have a car even with a

Japanese name on it.

Question: Do you hold the same animosity for the Germans?

Answer: No, because I don't know about what happened over in Germany, and of course

they were captured by white men, not Orientals. Orientals have an animosity towards whites.

I feel if they can get the best of them, they can.

Question: How do you feel nowadays about -- if you're doing business say, around town,

and where a Japanese-American citizen you're dealing with --

Answer: I don't mind them. I had a good friend out there, of course he passed away. He

was Japanese. I played golf with him. He was a nice guy. And his wife was nice. I know her

yet, she's still living. And I've always got along good with them. We had fun playing golf

together because he would always say "That's a rucky shot". (laughs) But he was -- he had

been put in the concentration camp over in Idaho and he could speak seven languages. So

they asked him to be an interpreter and he says well, I won't be an interpreter until you take

my wife out of that camp. And they did. And let them live where they were. But he was an

interpreter. He was a nice guy.

Question: So it sounds like your animosity is more towards a country --

Answer: Yes, hm-hmm, yes, that's a country.

Question: That seems like sometimes it would be a hard one to disassociate. I know that

some people -- their animosity was just extreme and it becomes a hatred with it.

Answer: Yeah.

Carl Kramp

Tape 2 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

3

Question: But it sounds like you don't really have -- you have an angriness towards the

country -- towards this mind set --

Answer: Yeah, hm-hmm. Younger people today, they don't know what went on. And so

it's my generation that would have against the Japanese, you might say. They're the ones that

we had to fight.

Question: That's why it seems like it would be hard today with a lot of the political

correctness and all that to say that's wonderful, but we also lived this, and that's a reality

also.

Answer: That's right.

Question: That needs to be respected. Like you said, you began to understand when you

saw the first person killed, the first person in your group was killed, that they're trying to kill

us.

Answer: Yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: And we're trying to survive.

Answer: That's right.

Question: When you think back, what was your hardest part about being in the service?

Answer: Well, the hardest part -- I liked the service. I did, I liked it. But I can't

remember the hardest part there in the States, anything like that -- I can't remember

anything like that. So, but I liked it. I liked the guys and everything, you know. It didn't

bother me. I liked the service.

Question: That's one thing when I talk to vets that -- the interesting thing has been is that

when you look at your full life, that World War II on the time line was this very small part, yet

there are these amazing bonds and relationships that were built between all the veterans.

Answer: Oh, yeah, hm-hmm. Well, I can't explain it -- I don't know how to explain it,

but I had no service hardship in the service or anything like that except when we was over

there fighting.

Question: When you hear the national anthem, the Star Spangled Banner played, what do

you feel?

Answer: I always stand for that. I feel -- I'm proud of it. In fact, the first -- we run up

an American flag -- the first one we could get over our camp, and brought tears to my eyes

when we did that. Cause we knew that -- what that meant -- that flag meant to us.

Question: Do you think that kids of today understand that? The freedom that you fought

for?

Answer: I don't think so. I don't think they do. They know what they have here, this

country. I don't -- they don't think about it enough, I don't think.

Question: Take it for granted.

Carl Kramp

Tape 2 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

4

Answer: They take it for granted, yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: If you -- do you think that there was a message from World War II for future

generations?

Answer: Well, I guess, try to get along with one another -- about the only thing I can

say. If you fight, why, you don't know what the heck -- like Israel and Palestine, over there.

I can't understand why people can't get along. Just because they're different religions is all.

And that's what bugs me is all these religious wars now. So I don't understand it.

Question: It's amazing how simple it is when you really get it down to the bottom line --

just try to get along.

Answer: Try to get along, yep. That's about the only thing you can do.

Question: Do you think war has a purpose or do you think war is --

Answer: Nobody wins from it. Nobody wins. You might save your country but you don't

win. Look at the people you lose. Good people, honorable people.

Question: Are you a hero? Do you think you're a hero?

Answer: No. I don't think I'm a hero or anything like that. I didn't do enough, I don't

think.

Question: Going and defending the freedom of your country -- you don't think that's

enough to --

Answer: Well, it's enough to do it but we -- we were disappointed that we couldn't do

more than what we were doing. We couldn't -- couldn't -- didn't have nothing to fight with,

but of course, in those days, why they -- I don't think they expected a war so quick.

Question: Did you lose any of your buddies over there?

Answer: I lost my future brother-in-law, one of them -- he passed away from malaria

Answer: And --

Question: He's the one in the picture?

Answer: He's passed away, too, but he come back. But his other brother, he -- he died

over there. Like they -- the Japanese put you in ten man shooting squads. Let one guy

escape then shoot the other nine. And one fellow from our battalion, from (inaudible)

California, he had to watch his brother be -- twin brother be executed by the Japanese -- one

guy escaped from his company -- his ten man shooting squad.

Question: I can't even imagine how you would face that -- I mean, that's the hardest thing

for me to understand as I interview the various vets is all that had to go on and how mentally

you toughened yourself up to deal with that.

Answer: There was four guys that was in the barracks next to me, we had bays, you

might call it. Not bays, but we slept. And they decided they'd go outside and see if they could

get some food. And -- because the Filipinos still had a little store outside the gates -- some

Carl Kramp

Tape 2 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

5

place outside the fence. This was right after we got to Cabanatuan. And so they went out and

they got caught. So the Japanese -- they tied them up to a post -- on the fence post, and

every one of them that went by beat them -- beat up on them a little while -- for awhile --

until they took them out that night and shot them.

Question: I don't understand that type of hatred. I mean, that's the only thing I could

guess it would be would be a hatred.

Answer: They had to dig their own graves and then they shot them. Another time they

just called a guy through the fence. The guard wanted him to come through the fence. The

guy went through the fence, well then the guard turned him in as escaping, and they made

him go out and dig his own grave and they shot him, too. And there was two Navy officers. I

know they escaped and they caught them. They brought them back to Cabanatuan -- they

beheaded them. Things like that went on at Cabanatuan. They'd cut off Filipinos heads and

stick them on the gate posts -- on the fence posts of the base -- on the fence posts.

Question: Do you think that was part of a psychological thing -- they wanted to let you

know that don't mess with us --

Answer: I guess so. I guess that was it.

Question: So it sounds like you chose to mind your P's and Q's and --

Answer: Oh, I did some rotten things, I guess, towards them.

Question: Was it -- did you know you were a part of history? This is what I've always

wondered. I mean, when we look back, you read about things and you go wow, that was

history. But when you were there, did you realize that you were changing the world?

Answer: No, no, we didn't. We didn't know. We didn't know what was going on in the

outside world. So we just sat alone. None of us got by ourselves or nothing -- we didn't know

anything was going on. No news got through or anything.

Question: What did you do after the war was over -- once you left there?

Answer: I -- well, the first year I just took that off. Took my $20 a week and stayed

home. My wife and I were married, and took $20 a week and stayed home and did odd jobs

and one thing and another. Then I went to -- went to work for the Sunshine Biscuit Company

and worked for them for a couple years, and then I got a job at Furman's Sanatorium worked

there, run the post office. So that's what I did there for seven years, and then I went into the

federal service, in the post office department. So, so I'm retired from the federal service.

Question: Did World War II change your life?

Answer: Oh, I think it did, yes, hm-hmm. I don't know what I -- probably been back at

Furman yet, if I hadn't changed -- if I hadn't done that.

Question: Did you -- a lot of people and being the way that World War II was, when they

got done, they came home, there was a country to run, and that part of their life was done

and they just moved forward. Is that kind of how you dealt with World War II?

Answer: Yes. Hm-hmm, hm-hmm.

Carl Kramp

Tape 2 of 2

Bristol Productions Ltd. Olympia, WA

6

Question: Fifty years is just back then.

Answer: It's back then, yeah, hm-hmm.

Question: Do you have -- I always ask this one -- this is one I forgot. Were there any

funny times? In the service?

Answer: Oh, yeah I can remember one time, the -- we was working down south of

Manila and we was knocking down rice paddies -- the Japanese wanted to build an airfield.

And we was working in gumbo mud up to our hips all day long. And the Japanese had put

rock in front of their guard house so they wouldn't get the dirt -- their boots dirty from the

mud. We'd wait until we got up in front of the guard house and we'd scrape that mud off, you

know, onto the rocks. So the company commander, not the company commander but our

group commander, Captain Ferrell, I can remember him yet -- he came to us and he told us

the Japanese wanted us to do an eyes left and goose step by the guard house in the morning.

So it rained that night and rocks were all slippery and everything. And we was barefoot. And

as we started by the guard house he says "Eyes left, goose step goose." And we all started to

laugh. (laughs) So we slipped and slid all over the place. They never did ask us to do that

again. (laughs) We didn't know if we were goose stepping.

Question: Glad they thought it was funny.

Answer: I don't know if they thought it was funny or not but they never did ask us to do

it again.

Question: Well, great.