![]()

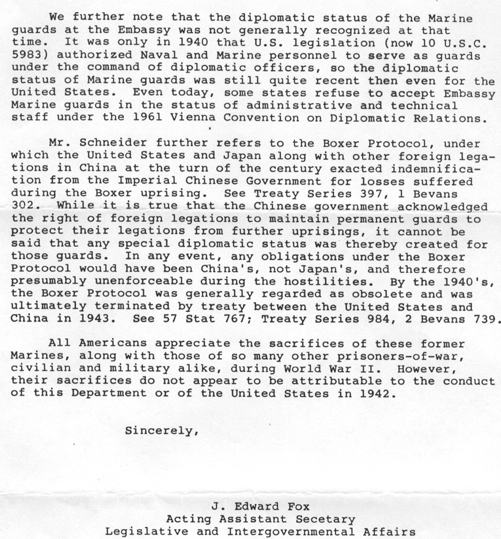

How is that these men came to be so vulnerable to capture when our war with Japan began? First of all note the above question includes the phrase "our war with Japan". The war in Europe began in September of 1939. The Japanese attacked China in 1937 and gained control of much of coastal China. Japanese forces were the ruling military authority in the major eastern cities, including Shanghai, Tientsin, and Peking. While most Americans consider December 7th, 1941 as the beginning of World War II, that date is only the beginning of our official involvement in the war. The North China Marines were not suddenly surrounded and captured on 8 December 1941, they had been surrounded by Japanese forces for years prior to that date.Great Britain pulled their forces out of Peking and Shanghai in August of 1940. German and Russian legation guards were removed prior to that date. When the British left there were approximately 1,200 Marines in Shanghai and 500 in North China (Peking, Tientsin, and Chinwangtao). Why were only 204 Marines captured and why were they captured at all? The final chapter seems to begin in August of 1941. American dependents were removed from China by presidential order in November of 1940. The units in Shanghai and North China were reduced over the next year but the units were maintained in place. Serious consideration for complete withdrawal of all Marine forces from China apparently began with a telegram, dated 14 August 1941, from the Consul General at Shangahi to the Secretary of State in Washington, D.C..highlights are my emphasis only - italiacs appear in the source,

Foreign Relations, 1941, Volume V. My comments and/or explanations are enclosed in the following [ ] The Consul General states "1083. Rear Admiral Glassford with the concurrence of the Commanding Officer of the Fourth Marines at Shanghai recommended late yesterday to the Commander in Chief of the Asiatic Fleet the withdrawal of American Marines from China. Asked before the despatch of the recommendation whether it had my concurrence I replied in the affirmative. Admiral Glassford and Colonel Howard feel that the postion of the Marines both here and in North China is becoming increasingly untenable from a military point of view. I concur in this view and I believe that the developments in the Far East during the past 2 months have made the position of the Marines also more untenable from a political point of view. In the case of an open break with but little or no forewarning the withdrawal of Marines would be difficult if not impossible. Administration and facility of the Marines at Shanghai is well known to the Department and to the Ambassador, but briefly, among the main factors, it might be pointed out that their functions are now becoming more and more those of a police force, thus increasing the possibility of serious incidents. Their presence apparently has not been a deterrent to the Japanese in implementing their economic policies in this area. Also the strength of the force would be wholly inadequate in the case of military operations directed against them by an organized force. It is especially requested that Admiral Glassford's recommendation be kept strictly confidential.Sent to the Department, repeated to Chungking and Peiping. Lockhart"

The US ambassador to China reacted on August 16, 1941. "Reference Shanghai's 1083, August 14, 4 p.m. The American Marines were originally despatched to China for the protection of American citizens resident there. In my opinion it follows that a major consideration in connection with proposals now to withdraw our forces should be the safety of the remaining Americans in China whom have good and sufficient reason for continuing and work here. The presence of our Marines in China, their conduct, and the manner in which their commanding officers have met the problems confronting them, has been one of the most important factors in insuring the safety of our nationals during past years.I do not believe that the Marines should be withdrawn from China unless and until it becomes evident to the American Government that relations with Japan have deteriorated to the point where a rupture appears inevitable, when, if the Marines are withdrawn, facilities should also immediatley be afforder for the withdrawal of Americans who do not elect to remain on their own responsibility. . . . Sent to the Department, repeated to Peiping and Shanghai. Gauss"

The Assistant Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs in Washington then enters the discussion in a memorandum on 20 August 1941. "Reference Shanghai's telegram no 1083, August 14, 4 p.m., Chungking'stelegram no. 353, August 16, 11 a.m., and the paraphrase of a naval telegram left at the Department of State by Secretary Knox on August 19.Admiral Glassford recommends, Colonel Howard concurs, and Consul General Lockhart concurs: that the American marines be withdrawn from China.Admiral Glassford's recommendation is based on his conviction that "despite Japanese Navy opposition, the Japanese Army will not long be restrained from taking over the International Settlement", that because of general deterioration in the local situation increasing demands are being made on the Fouth Marines to support the International Settlement police, which facts, he thinks, increase the chances that the marines may be involved in a serious clash, and that "there are generally grave potentialities in the present situation".Admiral Hart says, "I incline to support the above recommendation although I realize that many factors must be weighed in making a decision on this question." It should be noted that the reasoning given relates especially to the situation at Shanghai and the Fourth Marines located there; it does not contain express mention of the situation in north China and the small contigents of marines located there. Also, that Admiral Hart merely inclines to support the recommendation.Mr. Lockhart, in expressing his concurrence, says that in the case of an open break (with Japan) with but little or no forewarning, the withdrawal of the marines would be difficult if not impossible; that the presence of the marines at Shanghai has not been a deterrent to the Japanese in implementing their economic policies in that area; and that the strength of the contigent would be wholly inadwquate in the case of military operations directed against them by an organized military force.(Mr. Lockhart's comments are accurate but they are neither comprehensive nor penetrating. Taken by themselves, they do not weigh enough to tip the scales against the many considerations which can be advanced and which should be weighed against them.) The American ambassador, Mr. Gauss, who, from long experience, knows his China better than do any of the four officers mentioned above, and who has far greater responsibility in regard to the general political situation than have any of those officers, calls attention to the function of the marines, states that a major consideration in connection with proposals now to withdraw our forces should be the safety of the remaining Americans in China, states that the presence and the conduct of the said marines has been one of the most important factors in ensuring the safety of our nationals during past years, says that he does not believe that the marines should be withdrawn unless and until it becomes evident to the American Government that relations with Japan have deteriorated . . ." [The Assistant Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs, Mr. Adams, goes on at length. Notice he refers to the Marines in China as "marines", with a small m. The military and diplomatic personnel in China refer to the Marines as "Marines", with a capital M. Freudian perhaps, but does this have any meaning as to how the politicians in Washington perceived the Marines stationed in China?Mr. Adams also makes it clear he feels the civilian ambassador, located in Chungking, which is outside that part of China controlled by the Japanese, knows better than Rear Admiral Glassford, Jr., commander of the Yangtze Patrol, Colonel Howard, Commanding Officer of the Fourth Marines in Shanghai, and Consul General Lockhart, of the consulate in Shanghai, all of whom dealt directly with the Marines and the Japanese.]

In a follow up memorandum dated August 26, 1941, Mr. Adams says ". . . In as much as the American Marines are stationed in areas surrounded by Japanese-occupied areas . . . " and then later, " . . . those (American armed) forces may reasonably be described as under present conditions the keystone in the whole structure of the Occidental position in Japanese-occupied China . . ." [This gives us now an admittance by the Ambassador that Marines are an important factor in China and an admittance by the Asst Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs the Marines are surrounded by the Japanese and a further emphasis on their importance. Both of these points seem to be ignored a few months later when the decision to withdraw is made but no sense of urgency is given to that decision. ]Mr. Adams goes on to recommend ". . . the decision on the question of withdrawal of the American Marines ashore in China be held in abeyance pending certain developments in the field of high policy. . . . " He suggest plans be made to withdraw American nationals and " . . . thereafter to withdraw in an orderly manner the American Marines ashore . . . The further recommendation is made that decision to carry these plans into execution be not made until a conclusion shall have been reached that a rupture between the United States and Japan has become inevitable."(end of memorandum)

Mr. Adams issues another memorandum on September 10, 1941 "Reference Mr. Brandt's attached memorandum of September 8 in regard to possible withdrawal of Americans, including marines, from China covering further memoranda on the same subject. There is offered for consideration the suggestion that FE [Far Eastern Affairs Division, State Department] be authorized to discuss the matter orally with Captain Schuirmann of the Navy Department and to suggest to him that the Navy not make any definite plans in regard to which information might become public at present, but that the Navy Department keep in mind the question of affording Navy transport accommodations for American civilians in China prior to or at the same time of the execution of any decision to withdraw the American Marines ashore in China."

On September 15, 1941 the Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs to the Secretary of State, a Mr. Hamilton, wrote the following memorandum: "Mr. Secretary: I believe that there is no need for us to interpose objection to the Commander in Chief's proposal to reduce the number of Marines at Shanghai from 857 to 800 and those in north China from 260 to 200. If you concur, I shall so inform Captain Schuirmann with the request that this move be carried out in such a way as to minimize in so far as practicable publicity." The Commander in Chief referred to above is Admiral Hart, Commander in Chief of the U. S. Asiatic Fleet. Admiral Hart wrote a letter on August 28, 1941 to the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Stark. U.S.S. "Houston," Flagship, August 28, 1941.Subject: Withdrawal of U.S. Naval Forces from China1. During the past few months, the Commander in Chief has watched the position of the U.S. Naval Forces in China, particularly that of the Yangtze Patrol, the Fourth Marines and the MarineForces in North China, steadily deteriorate. On one occasion he recommended that the two Yangtze River Gunboats capable of making the voyage be withdrawn to the Philippines. That he has refrained from repeating that recommendation and from making a similar recommendation with respect to our Marines in Shanghai and North China has been due solely to the circumstances that first, the weakness of their military position is so obvious that it would be presumptuous to infer that the Department was unaware of it; and second, the pros and cons on the subject of their withdrawal go deeply into the field of high policy, concerning the aims and methods of which the Department is more completely informed than is the Commander in Chief. That he has now decided to set forth his views on the subject is because he believes the time has come when all the elements bearing on the position of those forces muct be closely examined, and when it should be made clear, beyond any possible misapprehension in any quarter, that every military consideration calls for their withdrawal. In other words, no single military advantage accrues to us by maintaining the Gunboats and Marines in china, for, in the event of war with Japan they would be quickly contained or destroyed, probably without being able to inflict even a comparable loss on the enemy. . . .

Admiral Hart continues on at length. In conclusion he states " . . . the Commander in Chief favors the withdrawal of all of our armed forces. If the Department is convinced that a complete withdrawal could create a reaction in China, Japan, or the United States, which it is most desirable to avoid, but agrees that the maintenance of considerably smaller "token" forces would serve the national interests equally well, the following action is recommended: (1) withdraw Luzon and Oahu, [gunboats](2) withdraw Marines from Tientsin and Chinwangtao, and(3) decrease the Fourth Marines to the minimum number required to support the contention that the question of evacuation of Sector Cast is not raised by our action. [sector C in Shanghai] The Commander in Chief estimates a force of two (2) companies would serve this purpose, but withholds a definite recommendation as to numbers pending the receipt of suggestions on this point from the Commanding Officer, Fourth Marines and the Commander Yangtze Patrol. 6. The urgency of delivery of this document is such that it will not reach the addressee in time via the next available officer courier. The originator therefore authorizes the transmission of this document by Pan american Lock Box from Cavite, P. I. to San Francisco . . . Thos. C. Hart"

On October 15, 1941, Mr. Adams, the Assistant Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs, put out this memorandum: "COMMENT ON MEMORANDUM FROM THE COMMANDER IN CHIEF, U.S. ASIATIC FLEET, TO THE CHIEF OF NAVAL OPERATIONS Subject: Withdrawal of U.S. Naval Forces from China, dated U.S. S. Houston, flagship, August 28, 1941. A. The signer of the present memorandum has seen during the past thirteen years many memoranda on the subject of withdrawal of American armed forces from China and he regards the memorandum now under reference, by Admiral Hart, as the most fully balanced, the most comprehensive, and the most objectively composed of any that he has seen of those prepared outside the Department of State. . . . " Adams goes on to present a history of US forces in China and their purpose. Marines had been in Peking since 1900, that in 1928 the US stationed a force of US Marines - although he again uses small case m - at Shanghai, in 1938 the US Army 15th Infantry was withdrawn from Tientsin, and replaced by splitting the Marine force in Peking and sending half to Tientsin. He mentions a policy since 1939 of reducing the number of Marines in China by technical attrition [not sending replacements for every Marine as individuals completed their assigned tours]. In 1938 the Marine forces numbered over 3,000 and now (Oct 1941) they numbered 1,200. He praises those forces for having " on many occasions made substantial contribution". He states he believes the matter of withdrawal of Marine forces from China was discussed with the President by the Secretary of State. If US forces are removed from China, Mr. Adams feels ". . . We should arrange to leave on duty at Shanghai, at Peiping and at Tientsin details of marines sufficient to continue the maintenance of our establishments of radio communication at those points. . . . "He faults Admiral Hart for not presenting any new evidence demonstrating the need for withdrawal of US forces. He mentions Admiral Hart wrote his letter in August and he (Mr. Adams) is now writing in October. " . . . Although nearly two months have since gone by, we have no information indicating that in the interval these forces have encountered any increased difficulty in the performance of their functions . . . it is perhaps pertinent to recall that in the course of consideration at intervals during recent years of possible reduction or withdrawal of American armed forces from China, suggestions have been advanced on several occasions that probably the last opportunity for unobstructed removal of such forces was (on each such occasion) close at hand. A "last opportunity" has not thus far developed. It is, of course, realized that it does not follow that the apprehended crisis may not some day (even soon) develope, but it is believed that what we know regarding current developments-including the most recent developments relating to the Japanese Cabinet-still leaves room for doubt that the long feared "crisis" is at this moment imminent. . . . " Mr. Adams closes this lengthy memorandum with the following: "It is fully realized by the undersigned and by officers present with whom matters above dealt with have been discussed now and previously that there has been, is and will be involved in maintaining American armed forces in China some amount of risk, and that no one can predict with absolute assurance that continued acceptance of this risk will not (nor that it will) result in some highly unfortunate encounter, and that we should not lightly persevere in the taking of such risk. . . . [the idea of risk by having forces in China over the previous hundred years is discussed] It is further believed that, also on balance, the calculable advantage of avoiding a disturbance of the situation such as withdrawal of those forces at this time would involve outweighs the envisageable risk which is involved in pursuing the stand-pat course, with qualifications suggested above. Without a one hundred percent withdrawal ( i.e., not even leaving behind details to maintain radio communications and perform custodial duties-e.g. at Peiping), there must continue to be some risk. The landed forces have been reduced during the last three years from a total of approximately 3,000 to a total of approximately 1,000. This number can be further reduced without a decided upon and obvious withdrawal. That procedure, it is believed, would for the present best meet the needs of the situation.This memorandum is and should be understood to be an expository contribution, the contents of which in no way commit the Secretary of State or the Department of State. Walter A. Adams"

So now we know what happened in North China on December 8, 1941 - a "highly unfortunate encounter". State Department language to describe the capture of 203 individuals and their imprisonment as slave labor for almost four years. Mr. Adams closing statement on his memorandum being only expository notwithstanding, the Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, followed with his letter to the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, on October 25th, ten days after the Adams memorandum. He states " . . . I find myself in accord with the general purport of and the specific suggestions made in the memorandum which I am sending here enclosed. . . . " Between October 25th and November 6th the Secretary of State apparently had new information presented to him as the following telegram demonstrates: The Secretary of State to the Ambassador in China (Gauss) WASHINGTON, NOVEMBER 6, 1941 - 7 p.m.259. Public announcement will be made in Washington shortly that the Government of the United States is giving consideration to the question of withdrawal of the american Marine detachments now maintained ashore in China a Peiping, Tientsin, and Shanghai.Sent to Chungking. Repeated to Shanghai and Peiping. HULL

This was followed by another telegram (262) on November 7th from Hull to Gauss. In it Hull states the President has approved " . . . withdrawal of marines from China. . . . " [In this case he uses the lowercase m.]" . . . Public announcement of decision will then be made in order that civilian nationals and others may have as much notice as practicable before withdrawal occurs. Thereafter withdrawal of the marines should be affected as soon as practicable. . . . "He goes on to say recommendations are being requested from senior officers in China on dates of withdrawal and shipping needed to accomplish the withdrawal.

On November 10th the Counselor of the Embassy in China sent the following telegram to the Secretary of State: 343. The American community at Peiping has reacted favorably to the President's remarks that consideration is being given to the withdrawal of the Marines from Peiping, reasoning that they would be ineffective because of smallness of numbers in any military engagement and that it would be a shame to incur any serious risk of their internment. Sent to the Department. Repeated to Chungking, Tientsin, Shanghai and Manila for Commander-in-Chief Asiatic Fleet. BUTRICK

At least the senior officers in China and the civilians the Marines were there to protect felt the Marines should be withdrawn before the obvious happened. Obvious to those in China, apparently not those in Washington. Now the decision has been made to withdraw the Marines and that decision relayed to China on November 7th. Why do only the Fourth Marines from Shanghai leave China before December 7th? (It is important to note the Fourth Marines were withdrawn from China only to encounter two possibilities in the Philippines, death in the fighting for Bataan and Corregidor or capture by the Japanese. So their withdrawal did not mean they fared any better than the North China Marines left behind.)

Telegram to the Secretary of State from Shanghai, November 13. 1945. Department's 262, November 7, 7 p.m. to Chungking. I regret the delay in replying to the Department's telegram but it was so badly garbled that repitition of the entire message was necessary. . . Marines and equipment can be moved from Shanghai within 5 days after transports arrive. However, date for despatch of transports will presumably depend on the duration of the interval the Department desires between the announcement that the marines will be withdrawn and the actual withdrawal. I do not believe that any aspect of the local situation makes it necessary to delay the departure of the marines. . . . Sent to the Department. Repeated to Chungking and Peiping. STANTON

Telegram from the Secretary of State to the Ambassador in China (Gauss) WASHINGTON, NOVEMBER 14, 1941 - 3 p.m.268. The President today made a statement to the press that the Government of the United States has decided to withdraw the American Marine detachments now maintained ashore in China at Peiping, Tientsin, and Shanghai, and that it is expected that the withdrawal will begin about November 25 and will be completed shortly thereafter. Sent to Chungking. Repeated to Peiping, Shanghai, and Tientsin. Peiping repeat to consular offices in Manchuria, including Darien. Shanghai repeat to Hong Kong and all consulat offices in Japanese occupied China. Hong Kong repeat to Saigon and Hanoi. HULL

[Chinwangtao is not mentioned because Marine personnel were only assigned there on a temporary basis from Tientsin. So mention of Tientsin includes Chinwangtao by inference.] telegram from The Counselor of Embassy in China (Butrick) to the Secretary of StatePEIPING, NOVEMBER 15, 1941 - 4 p.m.351. The Department's 262, November 7, 7 p.m. to Chungking.Colonel Ashurst has completed his survey of the Marines establishments in North China and is today making to Admiral Hart his recommendations in which I concur. Briefly they are as follows: (a) Withdrawal within 30 days after official notice to withdraw is received if no unforeseen complications are encountered in obtaining rail transportation; (b) Sentinels to remain: One radio operator at Tientsin and in Peiping three radio operators and six men for custodial service; . . . The remainder of the message discusses naval transportation for baggage and personnel, including civilians. It seems to me that not all decision makers involved in all locations were on the same page concerning the time of withdrawal. Ashurst is talking about withdrawal 30 days after official notice to withdraw, as if official notice has not yet been received He says that somewhere between 7 and 15 November. Given the garbled communciation mentioned on 13 November Ashurst is probably using a starting date for his 30 days as somewhere closer to 13 November. That means he sees withdrawal being completed by 13 December if official notice is given. Yet the President's public statement of withdrawal on 14 November gave 25 November as the beginning of the withdrawal and completion shortly thereafter. Even if the international dateline factor is considered Ashurst should have been given official notice by the time of telegram 351 of 15 November, Peking time.

Memorandum by the Assistant Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs (Adams) WASHINGTON, NOVEMBER 18, 1941 Captain Schuirmann telephoned to Mr. Adams and gave the following information:(1) the Navy has decided to withdraw the USS Luzon and USS Oahu from China and to withdraw the Commander of the Yangtze patrol.(2) The Navy is closing its purchasing office at Shanghai.(3) The SS Madison is scheduled to sail from Shanghai on November 26 and the SS Harrison on November 28. Passenger accommodations on these vessels are being sold as usual and the naval authorities are keeping the American Consul General at Shanghai informed. telegram from The Consul at Shanghai (Stanton) to the Secretary of State SHANGHAI, NOVEMBER 28, 1941 - 4 p.m.1791. First contingent of American Marines sailed yesterday afternoon on President Madison. Colonel Howard with remaining contingents sailed this afternoon on Harrison. Stirring scenes of farewell took place at the customs jetty upon the departure of the Fourth Marines. Diplomatic, consular, military, and naval representatives of various foreign governments were present to bid Colonel Howard and his staff farewell. There was also a large turnout of members of foreign and Chinese communities. Sent to the Department, repeated to Chungking and Peiping. Code text by air mail to Tokyo. STANTON

telegram from The Secretary of State to the Counselor of Embassy in China (Butrick), at Peiping WASHINGTON, December 2, 1941- 3 p.m.228. Department is informed that the Navy Department is chartering S.S. President Madison for one trip from Chinwangtao to Manila for the purpose of transporting to Manila the American marine detachments at Peiping, Tientsin, and Chinwangtao together with civilians who may wish to sail on the S.S. President Madison. The Navy Department states that it is expected that the President Madison will arrive at Chinwangtao on or about December 10 and will sail from Chinwangtao some 3 days later. The Navy Department stated that dmiral Hart is keeping the American diplomatic and consular officers concerned promptly and fully informed in regard to the matter. Sent to Peiping. Repeated to Chungking, Shanghai, and Tientsin. Peiping repeat to Tokyo, Mukden and Harbin. HULL

telegram from The Consul at Shanghai (Stanton) to the Secretary of State SHANGHAI, December 8, 1941 (received December 7 - 7:22 p.m.) Received telephone call at 4:15 this morning. A Japanese naval officer stated, "A state of war exists between my country and yours and I am taking control of Wake". All communications with Wake cut off and no further information is available regarding her. H.M.S. Petrel, small British gunboat, blew up at about the same time. Japanese in control of waterfront but have not taken over Settlement or French Concession. City quiet. All confidential codes and papers destroyed, including those aboard Wake except ditof [sic]. STANTON

The telegram of December 2 discussing naval transport for the withdrawal of the Marines in North China contained incorrect information. The book Captives of Shanghai by David and Gretchen Grover (1989) quotes from Captain Orel A. Pierson as having received orders by a ranking naval officer on Admiral Hart's staff to sail from Manila to Chinwangtao. He received these orders on December 3rd. Captain Pierson was captain of the SS Harrison, not the Madison. The Madison had already been released from Navy service after delivering some of the Fourth Marines to Manila from Shanghai. She was released to go on to Singapore and then the US.The Harrison left Manila for Chinwangtao on 4 December and was only off the Chinese coast near Shanghai on the morning of December 8 when a message was heard with the news of Pearl Harbor. She was to have arrived at Chinwangtao on the 9th of December. The captain and crew tried to outrun various Japanese ships but were unsuccessful and then ran their ship aground. Some crew were killed by their own ship's screws while abandoning ship. The remainder were captured and faced internment in civilian camps or imprisonment in POW camps. The authors blame "several uncoordinated and indecisive actions on the part of Hart's staff" for the failure of the Harrison to reach the North China Marines in time.

So why were 204 United States Marines captured on 8 December 1941?There were two separate views expressed by two separate groups concerning the status of the Marines in China in 1941. One group was the senior politicians in Washington and China, none of which saw the day to day circumstances in China concerning the Marines and the Japanese. The other group was senior military officials in China and those politicians located in the cities in which the Marines and Japanese co-existed, the decision makers on the scene. The politicians admitted the Marine"s presence and conduct had been one of the most important factors in keeping American citizens and property safe. But they also felt a need to continue that presence and conduct. The politicians admitted the Marines were surrounded by Japanese forces. They admitted the Marines were at risk for a "highly unfortunate encounter". But they felt there should be no definite plans to withdraw them, they doubted any crisis was imminent. The military and diplomatic personnel on site saw the Marine presence and conduct as no longer viable, the Japanese presence negated their effectiveness. They saw the Marine position as increasingly untenable, they should be withdrawn. They stated an open break with Japan would make withdrawal difficult if not impossible and their strength was wholly inadequate to defend themselves. War with Japan would mean their destruction or capture. They felt every military consideration called for the withdrawal of the Marines from China.Two very different views of the same set of facts. The opinions of those who dealt most directly with the problem were ignored. The political reality prevailed over the military reality. Those who referred to United States Marines as marines, with a lowercase "m", won their turf battle. As a result, two hundred and three United States Marines sank into a POW hell before war was declared and did not surface until after the peace treaties had been signed, almost four years later.

Click here to return to main page